Every day seems to bring a new headline about organised crime. Recently, coordinated attacks targeted multiple prisons in France, a striking reminder of how emboldened criminal groups have become.

Yet, as the focus turns again to crackdowns and security measures, a deeper question lingers beneath the surface. Are these events simply about crime — or are they symptoms of something far more troubling?

This week, I want to reflect on why criminal organisations are thriving. Why drug addiction is spreading beyond cities and into the countryside. Why violence among teenagers is rising to the point where lives are lost before adulthood.

What if the real danger lies not in the crime itself, but in what it reveals about us?

The rise of demand: Understanding the roots of drug use

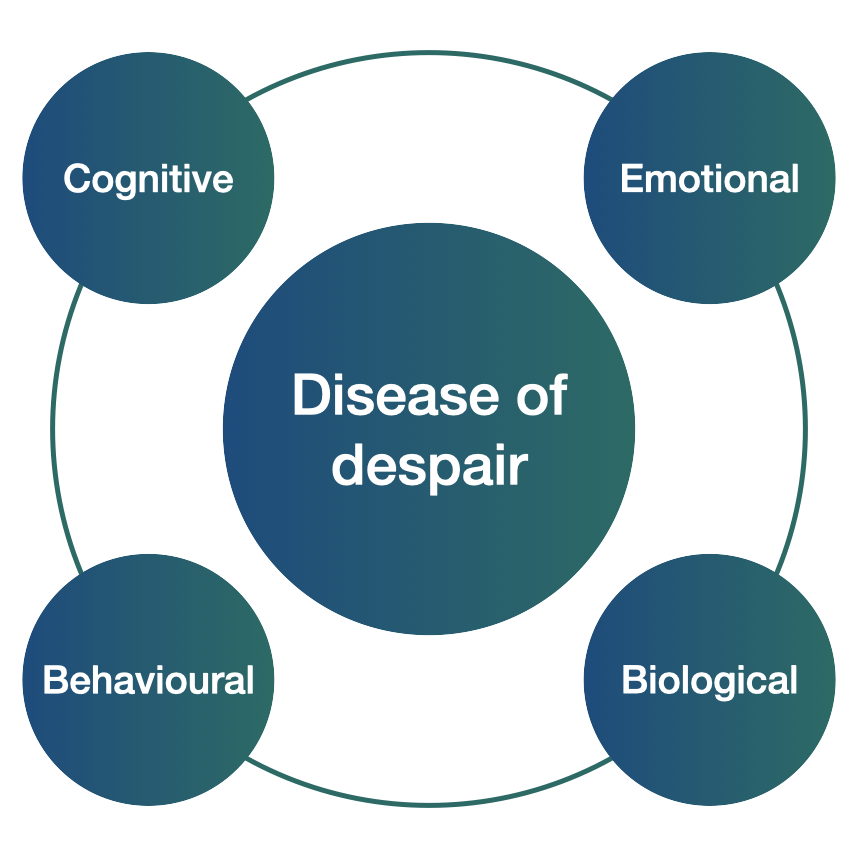

Behind every thriving drug market, there is a society struggling with despair. The term “diseases of despair” was introduced by Anne Case and Angus Deaton to describe the rise of deaths linked to suicide, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related diseases. These outcomes emerge where economic opportunities vanish and social bonds weaken.

Despair can take several forms:

- Cognitive despair: persistent feelings of guilt, defectiveness, and hopelessness, coupled with an absence of long-term vision.

- Emotional despair: deep sadness, loneliness, and emotional instability, often leading to a loss of future hope.

- Behavioural despair: a disregard for personal safety, risky decision-making, and tendencies toward self-harm.

- Biological despair: a physical disruption of the body’s stress regulation systems, causing exhaustion and vulnerability to addiction.

For a human being caught in despair, life becomes a matter of surviving the next day. Dreams and plans dissolve. A feeling of being defective takes root, leaving people vulnerable to anything that promises quick relief.

Drugs provide that false relief. They offer a rapid dopamine surge, a temporary escape from emotional emptiness, mental pain, or sheer exhaustion. When despair weighs heavy, the promise of immediate comfort becomes a powerful temptation.

Poverty remains a strong driver of drug use. A Swedish national cohort study found that those who experienced poverty during adolescence had a much higher risk of developing drug use disorders and facing drug-related convictions. In the United States, Case and Deaton observed that economic decline sharply increased deaths caused by substance abuse. Across very different societies, from Sweden’s welfare model to more liberal economies, the pattern repeats: when people feel trapped, despair drives them towards escape.

Social and peer pressures reinforce the pull. In adolescence, acceptance by a group can depend on mirroring its behaviours, including drug use. Even in adulthood, in high-pressure workplaces, normalised drug culture can turn an initial choice into a silent expectation.

Beyond poverty, industries such as restaurants, finance, and consultancy show high rates of substance use. Here, it is not hunger for survival but relentless performance demands that push people to seek artificial ways to cope.

In the end, the desire to escape — whether from poverty, from expectations, or from meaninglessness — is what fuels the rising demand for drugs.

Organised crime: Meeting the demand

Wherever despair creates demand, supply will follow. Organised crime thrives not because people are inherently evil, but because broken societies leave space for alternative economies to grow.

As drug use spreads, criminal groups step in to meet the need. The logic is brutally simple: where legitimate work opportunities are scarce or slow to reward, illegal markets offer faster and easier returns. Desperation, greed, and a lack of viable alternatives fuel the recruitment of young people into trafficking, dealing, and violence.

European cities like Antwerp and Rotterdam have become major hubs for cocaine trafficking, connecting Latin American cartels to European streets. Today, criminal organisations are deeply rooted across Europe, gangrening communities and weakening public trust in institutions. No country is immune. From France to Spain, from Belgium to Sweden, criminal groups expand their networks, exploiting every crack left by inequality and instability.

For many involved in these networks, the future feels too uncertain to matter. Long-term goals such as pensions, careers, or stable family life seem out of reach. Survival, status, and earnings ‘now’ are what counts, in a world where tomorrow is never guaranteed. Criminal organisations offer what society often fails to provide: a sense of purpose, quick earnings, and belonging — even if it comes with violence. When traditional paths to success seem closed, joining a gang can appear not just understandable, but rational.

As warlords thrive on conflict, drug lords thrive on despair. In both cases, violence becomes not a failure of morality, but a logical outcome when the social contract collapses.

When meaning, stability, and fair opportunities disappear, crime becomes an economy of its own — one that recognises only the laws of power and immediate survival.

Why repression is not enough

Faced with the rise of organised crime and drug use, governments often turn to repression. Stricter policing, harsher sentences, and tougher prison conditions are presented as solutions to restore order.

In France, recent measures have focused on isolating imprisoned gang members to break their networks. Across the Atlantic, the United States waged a “War on Drugs” for decades, filling prisons but failing to curb addiction or trafficking. Even in countries with the harshest penalties, including death sentences for drug offences, the trade continues undeterred.

The logic behind repression is simple: make the risks so high that potential offenders will choose another path. But when people are trapped in despair, the threat of punishment loses its power.

If survival is uncertain, if the future holds no promises, then the fear of prison — or even death — no longer acts as a deterrent.

Repression treats the symptoms, not the causes. It punishes those caught in the cycle, but leaves untouched the conditions that created the demand for drugs and the growth of criminal networks.

Criminal organisations thrive in broken environments. Unless inequality, hopelessness, and social disintegration are addressed, harsher laws will only treat the surface while the roots continue to spread.

If repression cannot heal a broken system, where should we turn to rebuild?

Building a way out

If repression cannot heal a broken society, then the solution must begin by repairing its foundations. Organised crime feeds on despair, inequality, and the absence of meaning. Rebuilding resilience requires more than harsher laws; it demands social, economic, and cultural renewal.

Reducing class inequality is crucial. Economists like Thomas Piketty have shown that without active policies — such as fair taxation and accessible education — wealth gaps naturally widen over time. When a society allows inequality to spiral, despair and social fractures follow close behind.

Yet opportunity alone is not enough. People need belonging. Strengthening local associations, from sports clubs to community groups, helps build the social ties that protect against isolation and hopelessness. Even self-entrepreneurs, by creating small businesses rooted in their communities, contribute to a sense of local pride and shared destiny.

We must also recognise how deeply the modern economy encourages instant gratification. In a world where convenience and dopamine-driven rewards shape behaviour, rebuilding resilience will require patience, meaning, and community spirit.

The future will not be saved by performance pressure, endless competition, or repression. It will be saved by restoring people’s sense of value — not just what they can produce, but who they are within their society.

If we want to starve the roots of organised crime, we must first offer people something stronger to belong to, and a future they believe is worth building.

Conclusion

Organised crime, addiction, and rising violence are not random outbreaks; they are warning signs that our society is faltering. Behind every statistic lies a deeper story of despair, broken trust, and lost meaning. If we keep fighting only the surface symptoms, we will never heal what is truly wounded.

You have a role to play. Each act of rebuilding — whether through fairness, belonging, or kindness — chips away at the foundations of despair. Change does not begin in distant institutions; it begins wherever someone dares to offer hope, a future, and a place where life feels worth living again.

I’d love to hear your thoughts. As always, you can reach me at night-thoughts@poyer.org — whether it’s criticism, a different view, or simply something to add to the conversation.

📚Further reading

- Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2020). Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Princeton University Press.

- Swedish National Study: Poverty and Drug Use Disorders Among Adolescents (available via PMC)

- Ehrenberg, A. (1998). La Fatigue d’être soi: dépression et société. Paris: Odile Jacob.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reports on inequality and crime (available at unodc.org)

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA): Drug markets and organised crime in Europe (available at emcdda.europa.eu)

- Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press.

- Report: Organised crime and the infiltration of legitimate businesses in Europe (European Parliament, 2021)