Technology is changing the way we think, connect, and grow—often without us noticing. This piece explores what we’re losing, what’s still possible to reclaim, and why it matters more than ever.

Last week, I heard a CEO explain how AI would soon solve their team’s capacity issues. They were excited about the boost in productivity. A few days later, my sister told me she hated AI—mostly because of cold calls and the loss of human connection. Two views, two different worlds. And I find myself somewhere in the middle.

I use AI tools almost every day. They help me rephrase ideas, explore topics, and get a clear overview when I need it. But even before using these tools, I had started to notice something else: my focus was shorter, I remembered less, and I became impatient with anything that didn’t get to the point fast enough. These changes didn’t come from AI—they came from how technology has gradually shaped my habits.

This is a look at how technology—and now AI—is quietly reshaping our mental habits, the way we connect, and the way we learn.

What follows is a personal reflection. Not a warning, not a rejection—just an honest look at where we are, what we might be losing, and what we could choose to protect. I don’t have all the answers, but I think it’s worth asking the questions now—while we still have time to choose how we shape this future.

A Mind Rewired – What Technology Is Doing to Us.

Before we talk about AI, let’s look at how technology has already reshaped the way we think, learn, and connect—with or without machines doing the work for us.

Digital Amnesia – Forgetting What We Used to Know

I used to remember phone numbers and PIN codes. Now, I mostly remember what to type into Google to find them again. And I’m not alone.

This shift in how we store and recall information is often referred to as digital amnesia. It describes the habit of forgetting things we know we can look up easily. It’s not about being careless—it’s just how our brain adapts when there’s no real pressure to remember.

A 2011 study led by psychologist Betsy Sparrow found that “people are more likely to remember where to find information than the information itself.” It’s practical—especially in a world full of data—but it changes how we build knowledge.

For me, it shows up most in everyday details. I still remember what matters for my work, especially the complex topics I deal with often. But when it comes to casual facts, I rely on search. It’s the same with directions. I grew up using real maps, but now it just feels easier to let Google guide me step by step instead of memorising the route.

That convenience comes at a cost. When we stop holding things in our heads, we lose some of the depth and connection that comes with learning. We might skip over the time it takes to absorb ideas properly—and that affects how we think over time.

It’s not just about forgetting. It’s about what we never fully take in.

Superficial Processing – Skimming Through Life

There’s so much information out there. Articles, podcasts, books, videos. I want to consume everything—and often, I do catch the essence. But I don’t always go deep.

This habit of taking in just enough to understand, but rarely enough to build lasting insight, is called superficial processing. It’s common when we read online, especially with long or unfocused texts. I notice it most with lighter books or lengthy articles. If a paragraph doesn’t get to the point quickly, I start scanning. Sometimes, I’ll just read the first sentence of each paragraph and move on.

Neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf, who studies how digital environments change how we read, says “we are becoming word spotters, rather than thoughtful readers.” That fits. I often know roughly what something is about, but I don’t retain much of it. It’s like reading the headlines of a conversation rather than the full exchange.

In some ways, this feels efficient. I’ve always been more interested in high-level ideas than tiny details. I also know how to work with others whose strengths complement mine. But even then, I see the risk: when I never stop to dig deeper, I limit how much I really understand—and how well I can build on it later.

We don’t absorb meaning by rushing—we absorb it by slowing down and paying attention.

Instant Gratification – The Cost of Having It Now

When I feel bored, I often find myself scrolling. It’s automatic—I don’t plan it. It just happens. I pick up my phone, and suddenly I’m lost in content. It fills the space, gives me something to react to, and then leaves me feeling mentally tired. I end up frustrated, not because I made a choice, but because I didn’t stop myself.

This is the core of instant gratification. It’s the tendency to seek quick, easy stimulation instead of slower, more meaningful effort. In a world built around speed and convenience, this response has become the norm.

Social media, home delivery apps, personalised feeds—everything is designed to keep us engaged without delay. The result? Our tolerance for waiting, for effort, even for silence, has shrunk. It affects how we learn, how we cope with discomfort, and how much attention we give to anything that isn’t instantly rewarding.

Researchers link this to our brain’s dopamine system—a cycle where small, fast rewards keep us coming back. It’s not that we’re addicted in a clinical sense, but that we’ve built habits around low-effort satisfaction. Tasks that require more time—like reading deeply or solving complex problems—start to feel harder, even when we want to do them.

When this becomes our default, it’s not just productivity that suffers. We lose the space for reflection. We stop enjoying activities that unfold slowly. And we forget what it feels like to focus without being nudged.

The more we grow used to ease, the more effort begins to feel like a burden.

Algorithm Reliance – Thinking Through a Filter

I often use ChatGPT to help me rephrase ideas or explore new topics. It’s helpful for getting a high-level view or structuring a first draft. But over time, I’ve started noticing how these tools are shaping the way I think.

When AI provides instant answers, it becomes easy to accept what’s offered as “good enough.” It skips the friction that often comes with thinking deeply or navigating ambiguity. For me, it’s just the beginning—I tend to ask more questions, challenge the output, and explore different angles. But I can feel the pull of speed and ease.

These tools are trained to simplify. The more we rely on them, the more we get used to binary views—good/bad, right/wrong, agree/disagree. Subtlety fades. We begin to lose our cognitive flexibility—our ability to hold complexity, to sit with uncertainty, to change our mind after hearing something new.

I also notice it in how I interact. If someone doesn’t quickly understand what I mean, I get more reactive. I expect precision, speed, and clarity—like the systems I use. That’s not how real conversation works. It takes patience, effort, and space to misunderstand and come back together.

The more we depend on algorithms, the less we practice independent reasoning. We become faster at finding answers, but slower at questioning them.

Convenience can be useful—but if we stop thinking for ourselves, we risk losing the ability altogether.

Loss of Empathy and Self-Esteem – Disconnected From Ourselves and Each Other

The more we communicate through screens, the harder it becomes to truly connect. We write quickly, send short replies, and often move on before thinking about how the other person might feel. We lose context. We lose nuance.

This has a direct impact on empathy—our ability to understand others emotionally. It also affects self-esteem, especially when our minds are constantly switching tasks or comparing our lives to curated images online.

Psychologist Sherry Turkle, in her book Reclaiming Conversation, writes: “We are tempted to think that our little ‘sips’ of online connection add up to a big gulp of real conversation. But they don’t.” These small, constant exchanges often lack emotional depth. And the more we rely on them, the more disconnected we can become from real human experiences.

I’ve seen this in myself—not as a lack of care, but as a drop in patience. I sometimes find it difficult to stay focused in conversations, especially when they don’t follow a straight line. I’m more reactive, less grounded. It’s not intentional. It’s just that the rhythm of tech doesn’t match the rhythm of people.

When our attention is split and we’re pulled in so many directions, we start to feel less in control. That can lower our sense of self-worth—not because we’ve failed, but because we feel mentally scattered, always catching up, never present.

Empathy needs time. Confidence needs focus. We lose both when we never slow down.

AI on Top – What Happens When We Speed This Up?

Speed vs. Understanding

A colleague once told me how AI transformed their development workflow. They used it to generate code, fix bugs, and deliver faster. It worked. They didn’t need to build the logic themselves, just prompt and review. It sounded efficient—and in many ways, it was. But I kept wondering: where’s the learning?

There’s a difference between getting something done and knowing how to do it. Using AI to help in a field you don’t plan to master can be a smart shortcut. But when it’s the core of your work, skipping the early steps risks weakening your foundation.

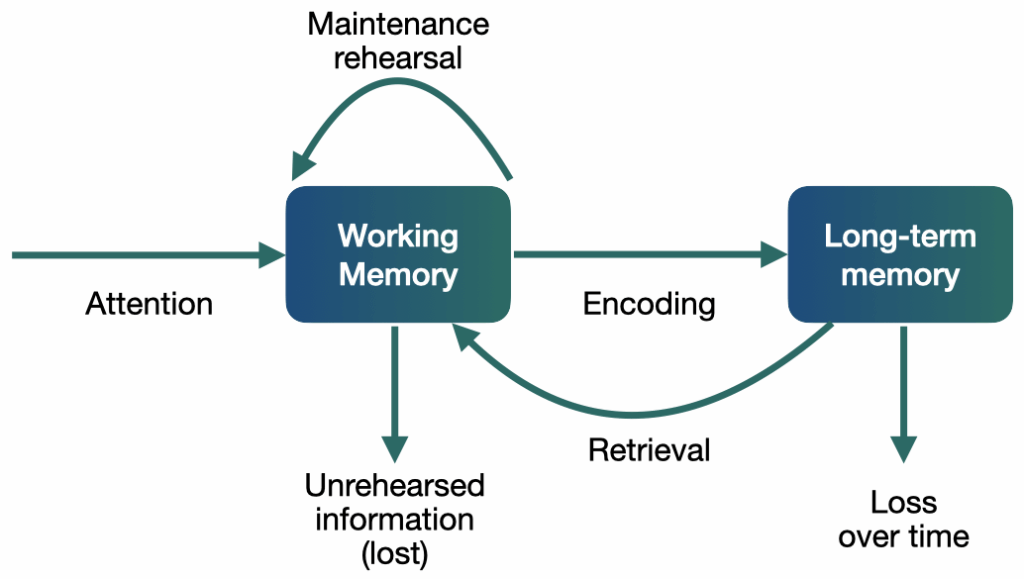

Felienne Hermans, Professor at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, references Cognitive Load Theory to explain how learning depends on the balance between challenge and mental effort. If a task demands more than our working memory can handle—because it’s either too complex or distracted by irrelevant details—then learning suffers. Researchers like Briana Morrison have worked on ways to measure this in beginner programmers, showing how fragile the learning process can be when the load is too high.

Daniel Willingham, a cognitive scientist, says it simply: “Memory is the residue of thought.” If we don’t engage deeply with ideas, we don’t retain them.

AI makes things faster, but not necessarily clearer. If we skip the thinking and let the system decide what’s correct or complete, we miss the part where understanding is built.

AI is a great partner—but if we rely on it too early or too often, we may lose the very skills we’re trying to develop.

Efficiency Without Exposure

AI also brings clear advantages in areas beyond code. For example, support teams handling travel disruptions or visually impaired customers now use AI to reduce strain on human staff. It helps with triage, summarises incoming issues, and provides quick responses in natural language. When volume is high or needs are specific, this can genuinely improve the experience.

But that same efficiency removes a layer of learning. Entry-level roles, often shaped by handling first-line support, have long been places where people developed product knowledge, communication skills, and empathy. Without that exposure, where does that learning happen now?

AI can simulate a human-like tone, gather information, and pass cases to the right team. But it doesn’t offer the same growth to the people it replaces. When we remove the need to talk to frustrated customers, search for patterns, or write up cases by hand, we also remove the process through which people learn to deal with ambiguity, discomfort, and real-life messiness.

These aren’t just tasks—they’re experiences that shape judgment and resilience. People used to build confidence by solving small problems, day by day. That’s harder to do if you’re only ever given neat summaries or final-stage requests.

When AI takes care of the first steps, we may be left with fewer ways for humans to learn what matters most.

The Risk of Shallow Expertise

As AI tools take on more early-stage tasks, the long-term risk becomes clearer: we start to build expertise without exposure. We produce more, but understand less. We interact faster, but connect less deeply.

This reflects the same patterns described earlier: we forget what we don’t practise (digital amnesia), skim rather than think (superficial processing), choose speed over patience (instant gratification), follow the suggestion instead of forming our own thought (algorithm dependency), and lose our human touch (empathy and self-esteem).

If AI continues to replace early learning steps—those shaped by mistakes, repetition, and effort—then the next generation of professionals may struggle to build true expertise. They may be skilled in using the tool, but not in understanding the system behind it.

This could deepen existing divides: a small group of people trained to go deep, and a wider group kept at the surface. That has consequences not only for education and work, but for society. As mentioned in a recent reflection on AI in sales, great professionals often succeed not because they know the script—but because they discover something human, something no machine can predict.

When we prioritise output over process, we lose the richness that only learning through experience can offer.

Why Change Feels So Hard

The Invisible Weight

Despite sensing the shifts in our attention and interactions, we often continue our routines. Personally, I notice that when I check my phone, I cycle through the same 3–4 news apps. A notification from one prompts me to check the others. Yet, on days filled with meetings, I can go without checking them, focusing solely on work-related apps. This habitual behavior illustrates how subtle these patterns are.

Culturally, we’ve normalized passive consumption. The phrase “Netflix & Chill” epitomizes this shift from active engagement—like reading or conversing—to passive viewing. Even meals, once social events, are now often accompanied by screens, diminishing genuine interaction.

These changes are gradual, making them harder to confront. The immediate comfort of digital engagement often overshadows the long-term implications for our cognitive and social well-being.

The Power Problem

The systems we use every day—social media, streaming, even productivity apps—are designed to hold our attention, not to protect it. The longer we stay, the more data we give, the more ads we see. That’s the business model. And those who control it have little reason to change.

This is the real power problem. While a few benefit from constant engagement, the rest of us adapt to a world where thinking clearly is harder and harder. Not because we aren’t capable—but because we’re constantly interrupted, nudged, and shaped by invisible systems.

And this divide is getting wider. In elite schools, students are trained to focus, to analyse, to build critical thinking as a skill. In many public schools, teachers and students face overwhelming pressure just to keep up. The same is true at home—some children have the space and support to read, reflect, or explore. Others come home to responsibilities, noise, or screens that fill the silence. They are left to grow up in an environment that doesn’t reward attention, let alone build it.

The risk is a new kind of inequality—not just economic, but cognitive. Some people will be trained to resist distraction, to focus, to question. The rest may never get the chance. Not because they’re less intelligent, but because the world around them makes it almost impossible to slow down and reflect.

This isn’t about who’s smart and who isn’t. It’s about who still has the space to think. If only a small part of society gets to build that strength, we aren’t just dividing opportunity—we’re dividing what it means to be human.

What We’re Really Losing

What’s at stake isn’t just our habits. It’s our ability to grow, relate, and make sense of the world.

We forget what we don’t practise. We skim instead of thinking. We lose patience for slow answers. We let systems do the sorting for us. We stop seeing people as people—and more as obstacles or profiles. These aren’t just side effects. They shape who we become.

Recent data shows children now struggle to focus for more than a few minutes at a time. This isn’t just about education—it’s about building the capacity to care, to reason, to create. Without those, what kind of future can we shape?

If AI accelerates all of this—removing friction, flattening nuance, answering before we’ve even asked—what happens to our sense of wonder? Or our ability to sit with uncertainty?

A world full of output, without depth. A society where fewer people can connect ideas, question what they’re told, or imagine something better.

We’re not just losing skills. We’re losing our grip on what makes us resilient, creative, and capable of change.

And if we don’t notice what’s slipping, we might forget we ever had it.

Reclaiming Our Mind: A Different Path Forward

Start with Ourselves

If we want to reclaim our minds, we need to begin by changing how we live—before we ask anyone else to change theirs.

I’ve started to place limits on my own screen time. I use downtime and app restrictions to avoid late-night scrolling. It doesn’t always work perfectly, but it helps. I’ve also carved out a routine in the morning: time for my body and my mind. Some days it’s yoga or core strength, other days it’s just cycling from one place to another—but the goal is the same: reconnect with the physical world, step out of the digital stream.

I’ve also taken on a weekly practice of reflection. Each Sunday, I try to write something meaningful—like this piece. It forces me to slow down, go deeper, and pay attention to what I’ve noticed during the week. I don’t expect to be perfect or consistent, but I try. And that, in itself, feels like progress.

These habits aren’t difficult. But in the world we live in, they might be some of the most important ones we can build.

What small change could you make this week to take back even a little space for your own attention?

Change What and How We Teach

Children aren’t born with short attention spans. We give those to them.

I was lucky to grow up before smartphones and social feeds. My childhood was made of games in the garden, boredom shared with friends, and limited TV—mostly the evening news. There was space to wonder, to wait, to invent. But today, many children are growing up in environments where boredom is filled instantly, often through a screen. And with that, something vital is being lost.

In France, phones are now being banned in schools. Some parents are pushing back the moment their child gets a smartphone. Others are learning to let go of their fear, giving their kids room to play, fail, and grow—without constant surveillance or stimulation. These are signs of change. But they’re just the beginning.

What we teach—and how we teach—matters. We need to teach children how to focus, how to ask questions, how to sit with not knowing. And we need to stop treating them like adults, or worse, like customers. Being a parent is not about pleasing. It’s about guiding. That means setting boundaries, creating structure, and showing what it means to struggle well.

There’s a growing shift in some circles where children are placed at the centre of every decision—as if their comfort and desires should guide everything. It’s sometimes called “child-led parenting,” but taken too far, it can blur boundaries that children actually need.

Children don’t need indulgence. They need adults who are willing to teach, to lead, and to hold space until they can stand in it themselves.

If we want a generation who can think, we have to show them how. Not by handing over control—but by walking with them until they’re ready.

Redesign the System

Reclaiming attention can’t just be personal. It has to be political. Cultural. Structural.

Ethical tech isn’t free. And it shouldn’t be. If you don’t pay with money, you pay with your time, your data, or your mental space. Real ethical platforms—ones that value your attention—need sustainable funding models. This could mean small fees, social subsidies, or public funding. But what they can’t be is free at the cost of your focus.

Regulation is the next step. The Digital Fairness Act, the AI Act—these are encouraging signs. But they need to go further. We should regulate attention pollution the same way we regulate carbon emissions. Because what’s at stake isn’t just privacy—it’s cognition. Empathy. Identity.

We need tools that ask for less, not more. Systems that support presence, rather than performance. Interfaces that create space, not pull us deeper.

We also need cultural change. Presence, patience, and deep work should be signs of strength—not inefficiency. What if the ability to reflect became aspirational again? What if we built a world where thinking slowly wasn’t a weakness, but a form of wisdom?

Because here’s the question we rarely ask:

If we don’t change what’s normal now, what kind of minds are we preparing for the future?

Conclusion

We’ve become used to a world that doesn’t ask much of us—at least not mentally. One where we can scroll instead of think, react instead of reflect, consume instead of connect.

But that world comes at a cost.

If we don’t notice what we’re losing—the ability to focus, to learn, to imagine, to care—we risk becoming strangers to our own minds. Passive participants in a world built by algorithms, but no longer shaped by human intention.

This isn’t a call to resist technology. It’s a call to remember who we are beneath it.

Because the most powerful thing we still have is the ability to choose how we show up, how we pay attention, and what kind of minds we pass on to the next generation.

And maybe the real question is this:

If we don’t protect the space to think—who will?

I’d love to hear your thoughts. As always, you can reach me at night-thoughts@poyer.org—whether it’s criticism, a different view, or simply something to add to the conversation.

Further Reading

- Felienne Hermans – felienne.com

- Daniel Willingham – Why Don’t Students Like School?

- Sherry Turkle – Reclaiming Conversation

- Cognitive Load Theory – https://theeducationhub.org.nz/an-introduction-to-cognitive-load-theory/

- Digital Fairness Act – https://www.digital-fairness-act.com/

- EU AI Act – EU Commission page