Tax season has arrived. Whether you’re in France, the Netherlands, Canada, or Sweden, it’s time to report what you’ve earned—and what you owe.

But tax isn’t just about filling in forms. It’s a moment where something bigger happens. We’re reminded that we’re part of a system. That someone is asking us to contribute. And that, whether we like it or not, we have a relationship with whoever’s doing the asking.

Sometimes that feels fair. Sometimes it doesn’t. A lot depends on how clearly we see who’s collecting the money, how the system works, and what we get back in return.

In this post, I want to explore how paying tax can create a sense of connection—or push people further away. I’ll look at what makes a tax feel legitimate, how visibility matters, and what other parts of life—like religion, business, and social media—can teach us about trust and contribution.

Because in the end, paying tax isn’t just about money. It’s about being part of something.

The Visibility of Tax and Why It Matters

Not all taxes feel the same. Some are quietly baked into prices. Others hit you right in the face.

Take sales tax, for example. In the United States, it’s added at the checkout. You see one price on the label, then a different total when you pay. In Europe, VAT (value-added tax) is usually included in the shelf price, so you’re less likely to notice it.

This small difference changes how we experience tax. In the US, the added cost is a moment of friction—a reminder that tax is part of the transaction. In the EU, that moment often disappears.

Some argue that visible taxes can help us pause and rethink what we consume—which, even unintentionally, might be good for the environment. After all, not every purchase is essential, and consuming less often means polluting less. I explored this further in Why Do We Want?.

But when it comes to visibility, income tax is in a different league. You know who’s charging it. You prepare the paperwork. You engage with the system, whether by logging into a portal or collecting receipts. Even in countries that automate the process, it still feels like a personal moment.

That effort creates something more than admin. It’s emotional. It can feel frustrating—but it can also create a sense of civic duty. You’re not just paying the government. You’re taking part in it.

When taxes are visible, they remind us of the structure we live in—and force us to ask whether we feel part of it.

Trust, Fairness, and the Social Contract

People don’t just pay taxes because the law says so. They pay when they believe the system is fair—and when they trust that what they give comes back in return.

Political scientist Margaret Levi explains that citizens are more willing to pay taxes when governments are legitimate, act fairly, and deliver real services. But those services also need to be visible. If you can’t see what your taxes are paying for, trust can fade quickly.

In countries like Sweden or Norway, taxes are high—but so are the benefits. Public healthcare, quality education, childcare, and well-kept infrastructure are all part of everyday life. People might not love paying taxes, but they feel the value, and that builds trust.

Now compare this to Nigeria, where tax compliance is low, and the public often sees taxes as unfair or pointless. With one of the lowest tax-to-GDP ratios in the world, Nigeria struggles to build trust in its system. Many citizens don’t see real services in return, and years of corruption have damaged public confidence. When people believe their money is wasted—or stolen—they’re far less willing to contribute.

The problem deepens when governments depend more on foreign aid than domestic taxes. Scholar Mick Moore has shown that states relying on external funding often have less incentive to build strong institutions or listen to citizens. But when governments need to raise money from their own people, they’re more likely to become accountable, responsive, and transparent.

This isn’t a new idea. The phrase “no taxation without representation” goes back to the American Revolution. It reminds us that taxation is never just financial—it’s deeply political. If people are to pay, they want a voice. And when that voice is heard, democracy grows stronger.

Paying for Value: What Governments Can Learn from Business and Media

Belonging often starts with contribution. Whether you’re giving money, time, or data—you’re taking part in something.

We see this in religion. In many communities, people give to their local church or faith group. In Germany, part of your income tax goes directly to your registered church. That contribution creates a sense of belonging. It’s not just about money—it’s about being part of a shared effort to help others.

But this only works if the group delivers. If the institution misuses the money, or stops supporting its members, people begin to walk away. The trust fades—and so does the sense of community.

The same thing happens in business. If you pay for a subscription, you expect value. If the service slips, you cancel. Even with “free” platforms like Facebook or X, you’re still paying—just with your data, your time, and your attention.

Back in the 1970s, media scholar Dallas Smythe introduced the idea of audience labour. He argued that audiences don’t just watch—they work. By watching ads, engaging with content, or simply scrolling, people generate value for media companies. Today, that concept has grown into what we call the attention economy. And it’s clear: when people feel their “contribution” is being misused—whether it’s money or data—they lose trust.

This is where governments can learn something. Like companies and communities, states need to recognise contributions, deliver visible outcomes, and make participation feel meaningful. Contribution is not just a duty—it’s a signal of membership. And membership means being treated with respect.

The EU and the Missing Link to Taxpayers

The European Union plays a key role in daily life, but many people mostly experience it through regulation and new rules. This visibility often comes across as distant bureaucracy—something opponents of the EU are quick to exploit.

In 1998, then-Taxation Commissioner Mario Monti proposed a European income tax to help bridge that gap. He argued it would “make the Union more visible to its citizens and strengthen the sense of belonging.” But member states pushed back, fearing a loss of sovereignty.

Since then, the EU has introduced complex tax initiatives like the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)and BEFIT, a plan to harmonise corporate taxation across member states. These projects matter—but for many citizens, they remain invisible. There’s no clear link between these taxes and their own contributions.

Meanwhile, countries like Canada offer a simple, relatable model. Canadians file one tax return covering both federal and provincial taxes. A similar EU-wide declaration could make Europe’s financial presence more visible—while also reducing income inequality and tax disparity across member states.

The EU could also explore clearer breakdowns of Value Added Tax (VAT), with one part for national budgets and one for the EU. Or it could send citizens a simple, yearly tax summary showing what went to the EU and what it funded.

Without that visibility, the EU feels like a system that makes rules, but not one we truly belong to. Events like Brexit, or the frustration seen in recent protests, reflect this disconnection.

If the EU wants to build not just policies but solidarity, it should make its financial relationship with citizens more open and direct. In times of global tension and instability, we need more than a common market—we need a shared identity, built on peace and unity in diversity.

Conclusion: Paying as Participation

In the end, taxation is never just about money. It’s about connection.

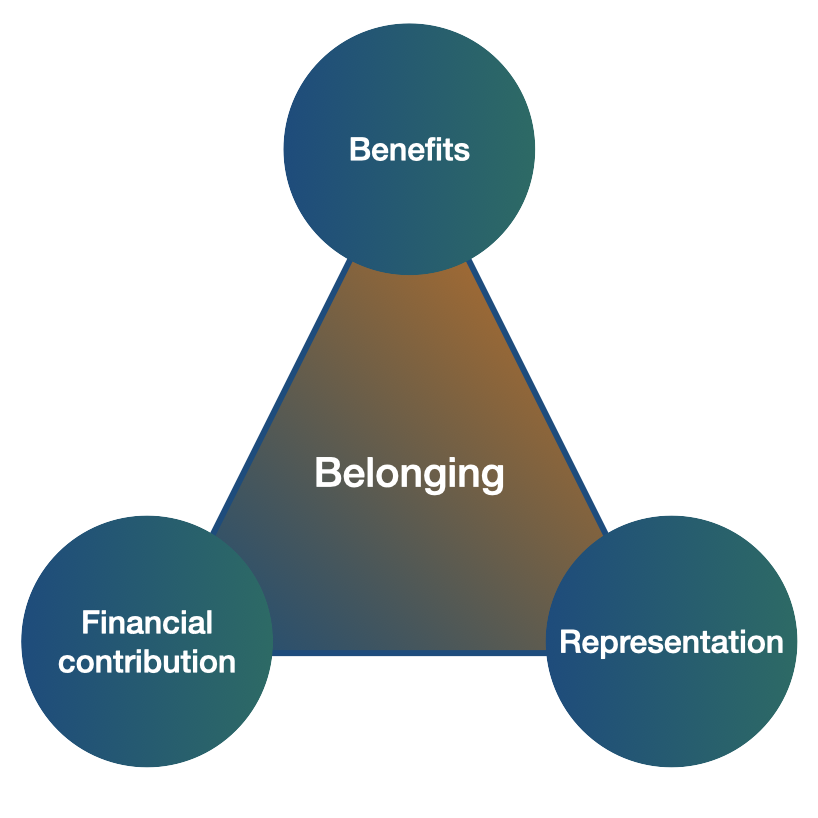

We accept taxes more willingly when they come from a system we trust—one that treats us fairly, delivers visible value, and gives us a voice. That’s as true for nations as it is for the EU. It’s even true in faith groups and digital platforms: if we contribute, we expect to belong—and to be respected.

Representation and taxation go hand in hand. When people are taxed without a say, they resist. When they see outcomes and have a voice, they participate. That participation strengthens democracy.

That’s what turns payment into something more than a transaction. It becomes a sign of membership—a quiet but powerful way of saying: I’m part of this.

As we rethink what tax means in today’s world, from digital economies to cross-border governance, one thing is clear: tax is not just about funding a system. It’s about building one we feel part of.

And for you, what do you think it would take for taxation to feel more like participation than a burden?

I’d love to hear your thoughts. As always, you can reach me at night-thoughts@poyer.org—whether it’s criticism, a different view, or simply something to add to the conversation.