This week, I was listening to Chaleur Humaine, a podcast by Le Monde, featuring Thomas Piketty—the well-known French economist. He was invited to speak about ecology and how the economy could play a role in addressing the climate crisis. Among many things he said, one idea stuck with me: his view that the income ratio between the lowest and highest earners should be limited to around 1 to 3, maybe 1 to 5. That got me thinking about something deeper—our possible addiction to poverty.

Income ratios are crucial in economic discussions because they help ensure cohesion within a society, fostering a sense of fairness and stability. This ties directly into the idea of the social contract, which I wrote about in a previous post on cohesion in society and business. Equitable income distribution isn’t just about economics—it plays a key role in maintaining social balance and promoting a sense of collective well-being.

So when Piketty pointed to that 1 to 3 range, I was intrigued. After some digging, I found that in France, after redistribution and social transfers, the ratio between the first and last decile is already around 3 (https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/7669723). That made me wonder: if we’ve already achieved that on paper, what exactly is he aiming at?

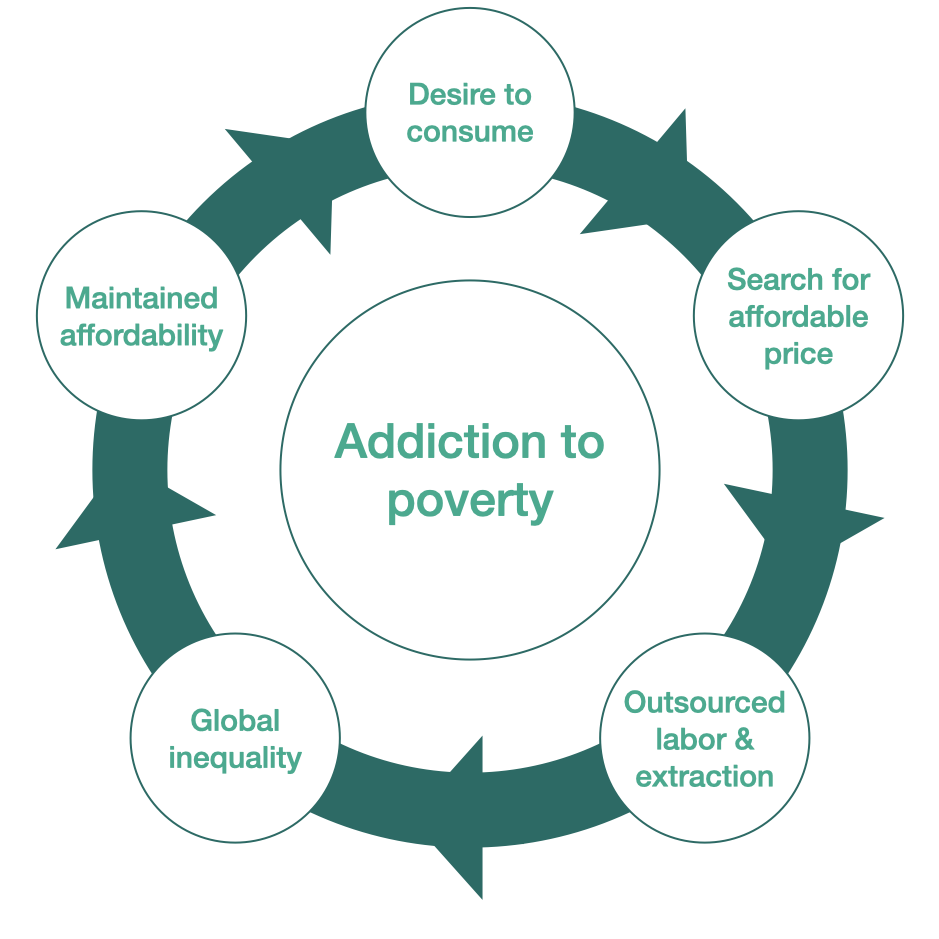

It got me thinking—not just about income inequality within national borders, but about how we even frame and compare wealth in a global economy that’s so tightly interwoven. And from there, a bigger question emerged: are we, in the wealthier parts of the world, somehow addicted to the poverty of others?

Rethinking Income Gaps in a Global Context

Piketty’s point about the income ratio made me curious—but then came another claim in the same podcast that left me puzzled. He suggested that 99% of the population could be employed in sectors like culture, healthcare, education, and transport, while only 1% would be needed for manufacturing and electric power. I’ll be honest, that didn’t sit well with me. Where is our food coming from in this scenario? Who’s building and maintaining the infrastructure? It felt a bit disconnected from the reality of how economies function. But then again, it’s a podcast—you can be put on the spot and say things that don’t land quite right.

Still, his comments made me reflect more deeply. In today’s globalised world, where goods and materials move endlessly across borders—from extraction to transformation, assembly, consumption and even recycling—how do we define an economy’s structure or fairness based solely on national data? Can we really evaluate income distribution by looking at one country in isolation, when supply chains and labour forces stretch across continents?

Take the income ratio again. If we use national deciles—say, the first and last in France—we might hit that 1 to 3 target. But what happens when we zoom out and compare the same deciles between countries? Is it fair to say the system is balanced when one country’s lowest earners are living vastly different lives from another’s highest earners, all while contributing to the same global economy?

That disconnect between national income statistics and global realities is where I think the conversation often loses its footing.

The True Cost Behind What We Buy

If we look closely at how products are priced today, the income someone earns doesn’t always reflect the value of the work behind the things they help create. Take a high-end smartphone, for example. The retail price might sit around $1000, but the estimated cost of manufacturing—including raw materials, transformation, and assembly—is closer to $416. Even when you add in shipping, design, R&D, taxes and retail costs, there’s still a hefty margin built in.

That margin doesn’t go to the workers assembling the device, nor to those extracting the raw materials. It flows higher up the chain—to intellectual property, engineering, branding, and ultimately shareholders. And that’s fine to a point—it’s how business models work—but it also highlights how disconnected the value of labour can be from the price of a product.

This model isn’t just limited to tech. It applies whether we’re talking about a car or a simple tea cup. Where something is produced, and under what conditions, drastically shapes its final cost and how much the people involved are paid.

If we then compare income levels across countries—for example, the last decile in China (around $9.1k per year, based on World Bank data: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/f66f7093d7be0141fe43156e5968c466-0070012024/original/CEU-December-2024-EN-Final.pdf) and the first decile in France after redistribution—the ratio is about 3. But when we compare the first deciles of each country, the gap widens dramatically. A ratio of over 33 between the lowest earners in China and the highest in France isn’t just an economic figure—it’s a mirror reflecting the imbalance baked into global production and consumption.

The real cost, then, is not just in dollars or euros. It’s in who is paid what, for which part of the process, and whether those doing the hardest work can afford the very things they help produce.

Local Living, Global Extraction

It’s true that many daily expenses—food, rent, basic services—are shaped by local conditions. So when we compare incomes between countries, it’s easy to argue that the differences are justified by different costs of living. And yes, to some extent, that’s valid. But the argument starts to fall apart when you consider how much of what we consume locally is made possible by labour and resources sourced globally.

Think of the food on your plate, the clothes you’re wearing, or even the cement used to build your home. A surprising amount of it comes from systems dependent on lower labour costs and fewer environmental regulations. Even staples like fruits, grains, or coffee often come from thousands of kilometres away, grown in regions where labour is cheaper and environmental oversight more lax.

If countries like France or the US had to extract, process, manufacture, assemble, distribute, and recycle all their own goods domestically—under their own labour laws and ecological standards—how much would we really be able to afford?

We’ve built an economic model that relies on this imbalance. Our lifestyle depends on it. We’ve externalised both labour and environmental impact—keeping our hands clean while keeping costs low. And in that sense, we are, knowingly or not, leaning on the poverty of others to sustain what we call “normal.” It’s not just about outsourcing jobs; it’s about offloading environmental and social costs.

So when we celebrate affordability or low prices, maybe we need to ask: affordable for whom? And at what cost, somewhere else?

Consumption and the Value of Wanting

If you remember my post Why do we want? , I explored how much of our desire to consume is driven not by need, but by comparison—seeing others with more, and feeling like we must catch up. That same impulse is everywhere: the nicer car, the sleeker phone, the new pair of shoes when the old ones still work just fine.

Do we really need that cute cup, when we already have one we like—dented, familiar, and entirely functional?

This constant cycle of wanting more reduces the value of each thing we buy. When everything becomes easily replaceable, we stop caring about quality or longevity. To feed that demand, production must scale, and prices must drop. And for prices to drop, someone, somewhere, has to earn less. So we find cheaper alternatives—whether it’s the materials, the labour, or the entire location of production—and keep the cycle spinning.

And that, again, keeps others in poverty. Not always directly, but structurally. The choices we make at the checkout are connected—however invisibly—to decisions made in boardrooms, factories, and fields across the world.

It’s not easy to break that cycle, especially when “more” is constantly marketed as better. But maybe it starts with noticing our own patterns, and asking if every want is really worth the cost—especially when that cost is someone else’s livelihood.

Currency, Fairness, and the Fragility of Global Comparison

The Limits of Comparing Incomes

We often compare incomes between countries using numbers that seem solid—figures in dollars or euros, rankings and ratios. But behind those figures hides something much less stable: foreign exchange rates.

Currency values depend on many things—trade balance, inflation, interest rates, political stability, and economic policies. All these factors shift constantly. Yet we use exchange rates to compare what people earn in different parts of the world.

That’s how we end up saying the first decile in China earns around $2.5k per year, or the last decile in Vietnam earns about $5.4k (https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099115004242216918/pdf/P176261155e1805e1bd6e14287197d61965ce02eb562.pdf). These numbers feel accurate, but they depend heavily on how we convert and interpret value.

Levelling the Playing Field?

What if, for a moment, we imagined that the revenue of the first decile was the same in every country? What would that do to our sense of fairness—or our ability to consume? Would people everywhere be able to afford the same basic needs, regardless of borders? Would the world feel more equal—or become more fragile?

We’d then have to consider those with no income at all. Many remote or informal communities still rely on trade and don’t fit neatly into income charts. What would this shift mean for them? And what about people in northern or Western countries who now enjoy cheap Christmas decorations, fast fashion, or that extra cute cup they don’t really need?

If we equalised incomes globally, would we simply recreate inequality at a national level? Would we start seeing ratios like 1:20 or even 1:50 within each country? That could bring new tension and social friction. Would nations begin to unravel—or just reorganise around income rather than geography?

It’s hard not to wonder if that’s already happening. The world seems to be reorganising—not through borders, but through spending power. We don’t just live apart; we consume apart.

And maybe that’s the uncomfortable truth. Maybe we, as humans, aren’t just indifferent to poverty. We might be addicted to it. We’ve built a system that needs poverty, feeds on it, and struggles to imagine another way.

The consequences reach beyond money. Every act of overconsumption—every product made cheap through inequality—comes at an environmental cost. We extract, pollute, and waste to maintain this system.

And in that sense, maybe Piketty isn’t wrong. Maybe our focus should shift—from production and profit toward culture, education, and health. Perhaps these are the pillars that should shape our lives and our societies.

Breaking the Loop – A Hopeful Direction?

Despite all the complexity and imbalance in the global economy, I do see signs that things might be shifting—however slowly. Nations like the USA and those across Europe seem to be rediscovering the importance of self-sufficiency. More and more people are recognising that local products must also be priced for local buyers—that people should be able to buy what they help create.

I’ve always believed that remuneration should match not just effort, but access. That if someone contributes to making something, they should be able to enjoy the benefits of it. But maybe that’s only part of the story. Maybe the bigger step is asking whether we even need everything we’re producing in the first place.

There’s something interesting about how instability, even when it feels disruptive, can sometimes open up new possibilities. Take Donald Trump’s trade policies, for example. While chaotic, brutal and protectionist, they may have unintentionally nudged parts of the global economy toward more regional thinking—toward shorter supply chains, local production, and a reassessment of what’s truly essential. Could that kind of disruption be what finally helps us reduce our dependency on global inequality?

That might be wishful thinking. But it’s a thought worth holding onto.

Because if we are truly addicted to poverty—if the global system is built around keeping costs down by keeping others down—then breaking the loop won’t be easy. It requires a change not only in policy, but in mindset: valuing sufficiency over excess, and fairness over efficiency.

I’d love to hear your thoughts. As always, you can reach me at night-thoughts@poyer.org—whether it’s criticism, a different view, or simply something to add to the conversation.